Alfond Collection: Artists K-L

From Deborah Kass to Al Loving, explore the works of artists K-L in the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art.

PLEASE NOTE: Not all works in the Rollins Museum collection are on view at any given time. View our Exhibitions page to see what's on view now. If you have questions about a specific work, please call 407-646-2526 prior to visiting.

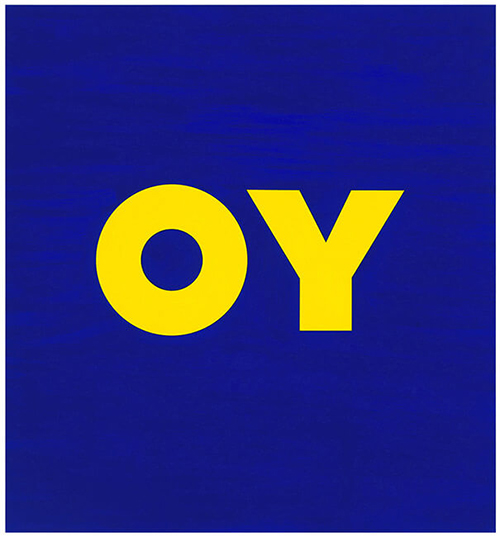

Deborah Kass

(American, b. 1952)OY, 2011

Screenprint

21 1/2 x 20 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.61. © Deborah Kass / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Appropriation art—which involves borrowing and reworking existing media—provides the framework for Deborah Kass’s paintings. Her work juxtaposes masterpieces by male artists with equally familiar images culled from advertising, film, and pornography to make not-so-subtle statements about the gendered messages disseminated by high art and popular culture alike. Kass suffuses every image she touches with a Pop art sensibility inspired by Andy Warhol, who has been a longstanding reference for her. She directly draws on his imagery and style, and her close engagement with his work was showcased in her retrospective at The Andy Warhol Museum, Deborah Kass: Before and Happily Ever After (October 27, 2012-January 6, 2013). Bright colors, bold text, and recognizable content introduce an element of play that makes her incisive feminist commentary easier to digest.

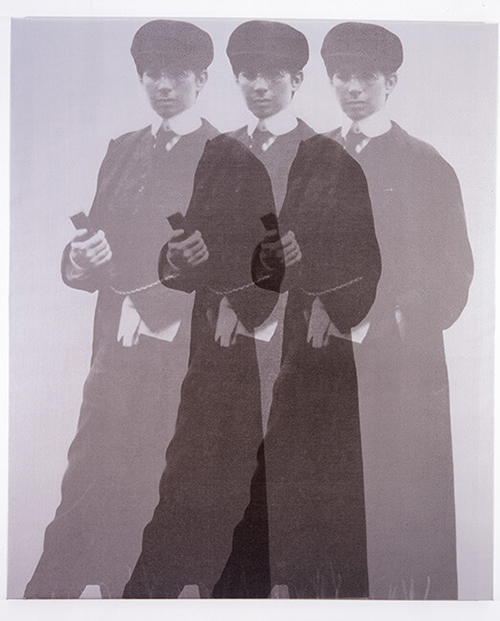

The implications of substituting the Streisand/Yentl figure for Elvis are manifold. Kass’s adulation of the gender-ambiguous character affirms lesbian desire and proposes a new model of female spectatorship. The three identical, overlapping, translucent figures cannot be visually pinned down, much like Yentl’s own gender and sexuality.

Kass’s pendant prints YO (2011) and OY (2011) likewise address Jewish contributions to popular culture. The simple letters in complementary colors recall the onomatopoeic exclamations that Pop borrowed from comic books, while their simple reversal prompts the viewer to question their meaning. This impulse to question the unspoken assumptions of visual culture is a driving force in Deborah Kass’s work, which updates feminist concerns for a contemporary audience.

--Sarah Parrish

Deborah Kass

(American, b. 1952)YO, 2011

Screenprint

21 1/2 x 20 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.62. © Deborah Kass / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Deborah Kass

(American, b. 1952)Triple Ghost Yentl (My Elvis), 1997

Silkscreen and acrylic on canvas

72 x 64 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.91. © Deborah Kass / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

A revisionist approach to art history has been a constant source for feminist artists and scholars since the late 1960s. Feminism has undergone drastic changes in the past four decades, however, and one characteristic of more recent incarnations of feminism is the recognition that gender intersects with other forms of identity. Kass’s complex identity as a woman, a Jew, and a lesbian informs pieces like Triple Ghost Yentl (My Elvis) (1997). Here Kass depicts Barbra Streisand in the film Yentl (1983), in which Streisand played a Jewish woman who cross-dressed to become a Talmudic scholar. Kass performs a parallel act of artistic transvestitism by placing herself in the role of Andy Warhol, who used an identical composition and process to depict Elvis in the mid-’60s.

--Sarah Parrish

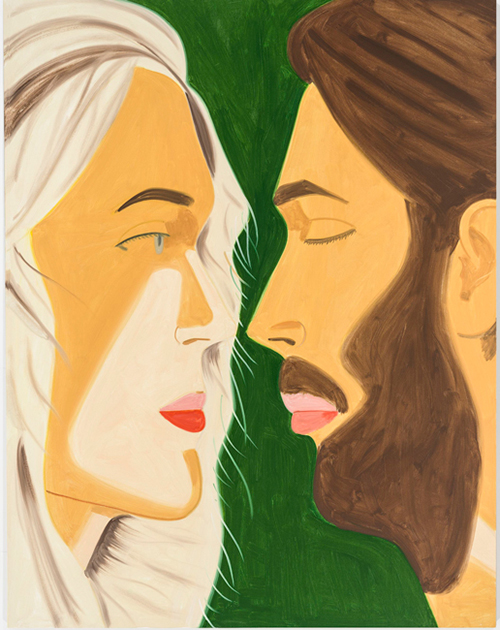

Alex Katz

(American, b. 1927)Amanda and Kyle, 2016

Oil on linen

108 x 84 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.6.3. © Alex Katz / Licensed by VAGA, New York.

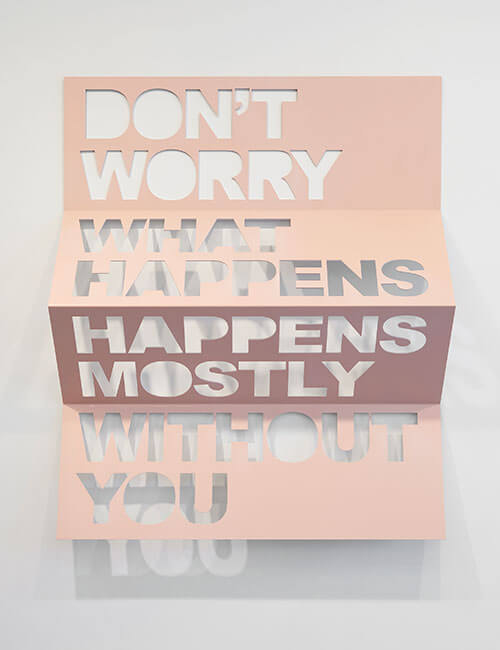

Matt Keegan

(American, b. 1976)Don't Worry (a sculpture by Matt Keegan, from a poster by James Richards, of a poem by Josef Albers), 2012

Stainless steel, spray finish

40 x 48 x 10 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.103. Image courtesy of the artist and Simone Subal Gallery, New York.

A significant portion of our daily conversations contain stock phrases; “the plot thickens,” “think nothing of it,” “we have to stop meeting like this.” It’s easy to forget that these sentences come from somewhere; that they may have first emerged in a novel or play or movie. Every time we use them, we’re referring back in time, drawing on the resources of the past to fill the space of our present. Matt Keegan & James Richards attempt to materialize this process of referentiality and appropriation, freezing the moment when words pass between us and when phrases unfold into new contexts.

Independent practitioners of contemporary Conceptual art who engage in appropriation and found “material,” Matt Keegan and James Richards join here to create Don’t Worry (2012), a wall-mounted sculpture that considers communication, interpretation, and understanding. The short phrase “Don’t worry, what happens happens mostly without you” is laser-cut onto stainless steel. The format, font, and layout are all directly copied from a poster originally made by James Richards. Richards, in turn, had taken the words from a poem by German artist Josef Albers. Yet the poem, in its original German, read “calm down” (beruhige dich) instead of “don’t worry.” At what point was it replaced with “don’t worry”? By the translator? By Richards? The alteration is subtle, but its presence alerts us to the evolution of meaning in repetition. Keegan’s sculpture isn’t the same as Richards’s poster, and Richards’s poster wasn’t the same as Albers’s poem. The repeated transformation of the phrase echoes the sentiment it contains: what happens to an artwork, after completed, happens without the artist and outside of their control. Such is appropriation—what was pure language for Albers became graphic representation for Richards, and the flatness of Richards’s poster was remodeled into a sculptural object in his collaboration with Keegan.

Borrowing, citing, and quoting have always been essential to art and text. What Keegan & Richards remind us is that when language is the art, the viewer is essential to the work’s completion. Similar to the experience of pieces by Conceptual art founders such as Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner—both of whom are represented in the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art for Rollins College—it is through the viewer’s digestion and analysis of the selected language that the piece is activated. In this case, is the “don’t worry” ironic? Comforting? The work reminds us of a game of telephone, where language is transformed by the listener interpreting the voice of the speaker.

--Kelly Presutti

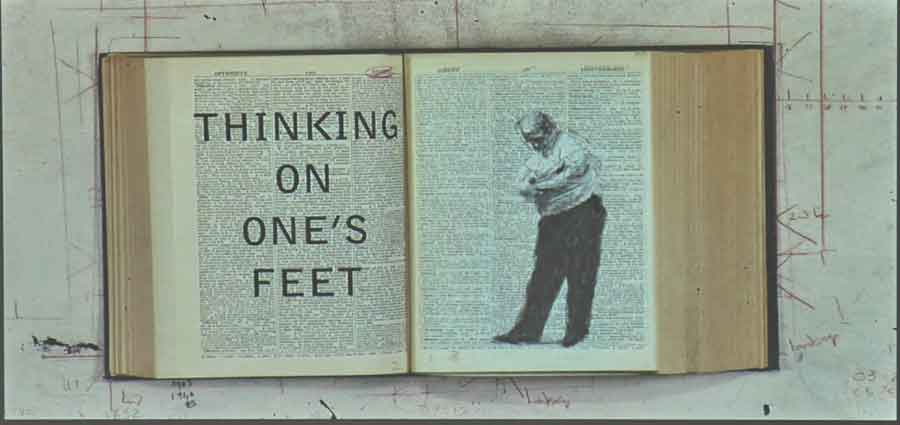

William Kentridge

(South African, b. 1955)Second-Hand Reading, 2013

Single channel HD video

7 min.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.142. Image courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

William Kentridge’s films, videos, prints, drawings, and set designs generally relate either explicitly or indirectly to his home country of South Africa. The stop-motion films and videos he has made for twenty-five years address such weighty themes as time, memory, and colonialism. The film Second-hand Reading (2013) shows the rapidly flipping pages of Cassell’s Cyclopedia of Mechanics, originally published at the turn of the twentieth century. On the pages of the book, Kentridge has drawn a series of images and words that are animated as the pages flip. Haunting music by South African artist Neo Muyanga plays in the background. In his practice, Kentridge—eager to enhance his work by combining his expertise with the knowledge and talents of others—collaborates with a wide range of individuals, such as scientists, composers, and designers.

Kentridge is interested in parallels between books, trees, and human knowledge or thought. Reference books have long aspired to present comprehensive lists of vocabulary or concepts, and Kentridge often uses the pages of such books as the grounds for his drawings, noting that they provide a “layer of thought” onto which he can add his own.1 Indeed, a hand-drawn figure of Kentridge that paces across the pages of Cassell’s Cyclopaedia with his head bowed and his hands in his pocket appears to be deep in reflection. The words and images that appear on the pages might refer to thoughts: some, such as the phrase “whilst spreading the apricot jam,” seem mundane and personal, while others, such as an image of a man lying dead in a landscape, seem more consequential and relevant to an entire society. Trees have served as metaphors for human knowledge since the writing of the Old Testament, in which Adam and Eve taste fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Like Kentridge, Denis Diderot connected the concepts of the reference book and the tree in his eighteenth-century Encyclopedia, the first volume of which includes a frontispiece showing the “Tree of Knowledge.”2

Kentridge also probes the relationships between trees, books, and identity. He sees the building of a personal library as a way for one to construct a sense of self. Similarly, he views trees as “a kind of outsized self-portrait.”3 We might interpret the trees in Second-hand Reading, which are modeled after those found in Johannesburg, as references to Kentridge’s own likeness.4 Images of trees flow into drawings of the artist, becoming a kind of double for him. This doubling suggests that the artist is on the one hand an individual, while on the other inseparable from the country in which he was born and continues to live. Perhaps the tree represents the fact that, like Adam and Eve, South Africa has lost its innocence.

--Davida Fernández-Barkan

________________________________

1William Kentridge, “Second Hand Reading,” video, 42:48, the University of Rochester, posted by InVisible Culture, September 19, 2013, http://vimeo.com/78123839.

2Stephen Cummings, ReCreating Strategy (London: SAGE Publications Inc., 2002), 48.

3Kentridge, “Second Hand Reading.”

4Brian Boucher, “The Pages of a Mind: Interview with William Kentridge,” Art in America, accessed November 19, 2014, http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/interviews/the-pages-of-a-mind-interview-with-william-kentridge-/.

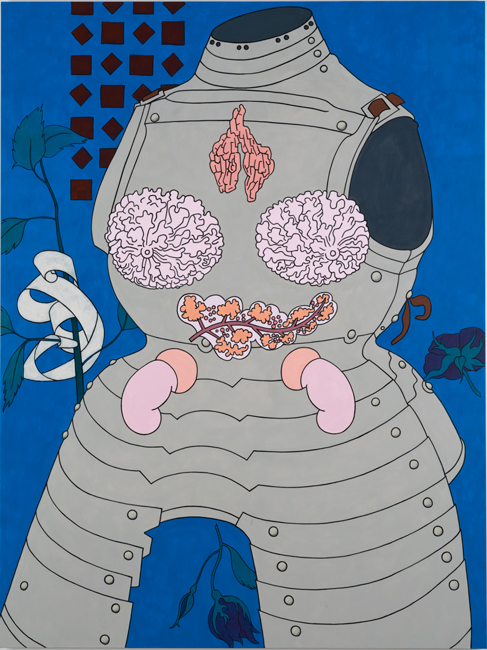

Caitlin Keogh

(American, b. 1982)Renaissance Painting, 2016

Acrylic on canvas

84 x 63 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.15. Image courtesy of the artist and Bortolami, New York.

Josh Kline

(American, b. 1979)Reality Television 7, 2019

Nylon flags, polyurethane, epoxy, microfiber, mounting hardware

26 x 44 1/8 x 6 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2019.2.26. Image courtesy of Modern Art Ltd.

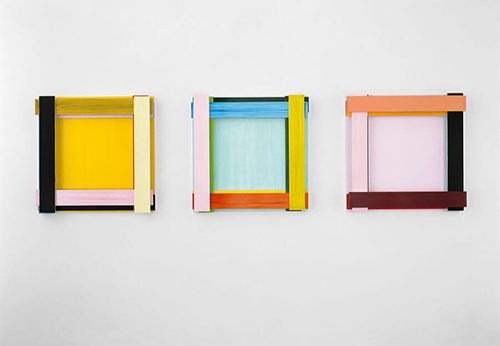

Imi Knoebel

(German, b. 1940)Alte Liebe, 2011

Acrylic on aluminum

33 1/2 x 130 x 4 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.117. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Christian Lethert, Cologne. Photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne

Since the beginning of his artistic career in the late 1960s, Imi Knoebel’s work has been concerned with the end point of painting. Though he studied with Joseph Beuys at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, he chose not to follow Beuys’s practice of “social sculpture.” Instead, Knoebel absorbed from his teacher the possibility of an open artistic practice and new beginnings. This allowed him to reconsider painting as a medium by investigating its fundamental elements—structure/support and surface.

Inspired by cool American Minimalist aesthetics, as well as the purity of Kasimir Malevich’s Suprematism, Knoebel’s first major work, created in 1968, was an installation of 77 geometrical objects crafted from fireboard titled Raum 19. In this piece, Knoebel pulled apart the most basic aspects of painting—stretcher bars, rectangular volumes, planar shapes—and presented these essential ingredients in deconstructed form. This work marked the start of Knoebel’s preoccupation with the significance and limits of conventional painting, which has lasted throughout his career.

In Alte Liebe (2011) Knoebel again explores the relationship between surface, frame, and color. Three panels hang contiguously on the gallery wall. The interplay of hues echo each other across distinct but related forms. Perched atop the monochromatic back panels of vibrant yellow, cool turquoise, and subtle pink are segments of aluminum stretcher bars all painted in alternating colors of varying intensity; black, blue, orange. Arranged in specific spatial relations, their interlocking forms create a dynamic composition and shift the attention of the viewer from the painting’s center to its periphery. This configuration frames viewers’ perceptions, inviting them to encounter color as volume.

Although Knoebel’s works can be understood as paintings, they also aspire to undermine the status and role of that storied medium. His simple yet highly intriguing forms evade straightforward medium specificity. Knoebel performs an architectural operation, positioning the aesthetic experience in relation to space.

--Martina Tanga

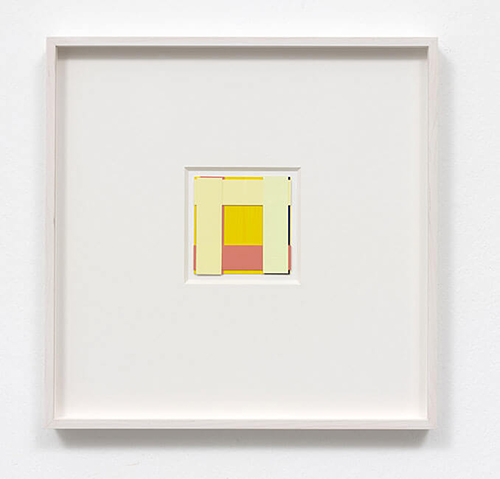

Imi Knoebel

(German, b. 1940)Faces 01, 2002–2011

Acrylic on plastic film

3 x 3 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.143. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Christian, Cologne, Photo credit: Simon Vogel, Cologne.

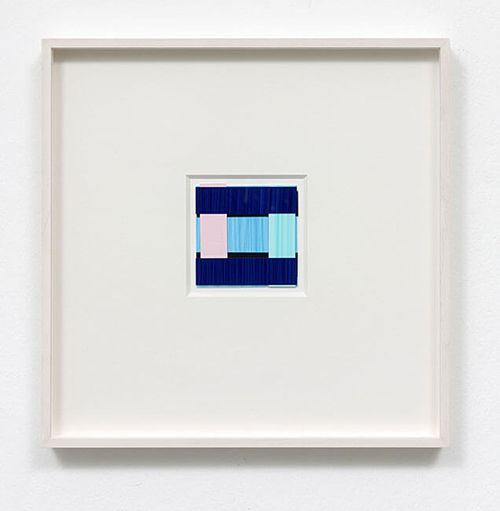

In 1977, German painter Imi Knoebel made a decision that altered the course of his career—he introduced color into his practice. Whereas before his work was limited to black, white, and brown, his project 24 Colors—for Blinky (1977) engaged the full color spectrum. Since then, Knoebel has produced abstract paintings to systematically analyze the interface between color, space, and shape. His exploration of these basic formal elements led him to move beyond the rectilinear format of conventional painting in favor of shaped canvases. By layering and arranging these shaped paintings, he could not only imply depth through advancement and recession of adjacent colors, but also achieve actual depth through the three-dimensional accretion of painted surfaces.

This dynamic is at play in Faces, a series that represents the most recent developments in Knoebel’s sustained investigation into the optical and emotional effects of color. The Faces are formed from strips of plastic film streaked with bright brushstrokes, overlapping at right angles to form a lattice, each in a distinct color scheme. In Faces 28 (2002/2011), two horizontal strips of sky blue are sandwiched between cream and orange verticals on the left and red verticals on the right, all on a ground of bubblegum pink. The same shade of sky blue appears in Faces 11 (2002/2011) amidst a much cooler palette of white, royal blue, and black. As the juxtaposition of these two works reveals, each Face has a unique personality, and indeed, the titles invite viewers to interpret these as anonymous yet individuated portraits.

Knoebel himself is an important “face” of German postwar art. Alongside Blinky Palermo, Jörg Immendorff, Imi Giese, and Katharina Sieverding, Knoebel studied under the influential artist Josef Beuys. Superficially, Knoebel’s reductive formalism shares little with Beuys’s political orientation and use of tactile media. Instead, Knoebel’s paintings, installations, and light projections seem more closely related to the Russian avant-garde painting of Kazimir Malevich, whom Knoebel cites as a major source of inspiration. Yet Faces and related works evince a Beuysian sense of democracy and complexity, as Knoebel restructures the conventional portrait genre to posit new models of subjectivity.

--Sarah Parrish

Imi Knoebel

(German, b. 1940)Faces 06, 2002–2011

Acrylic on plastic film

3 x 3 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.144. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Christian Lethert,Cologne, Photo credit: Simon Vogel, Cologne.

Imi Knoebel

(German, b. 1940)Faces 11, 2002–2011

Acrylic on plastic film

3 x 3 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.146. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Christian Lethert, Cologne, Photo Credit: Simon Vogel, Cologne.

Imi Knoebel

(German, b. 1940)Faces 28, 2002–2011

Acrylic on plastic film

3 x 3 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.145. Image courtesy of the artist and Galerie Christian Lethert, Cologne, Photo credit: Simon Vogel, Cologne.

Lucia Koch

(Brazilian, b. 1966)From the series Fundos: Café Extra-Forte, 2011

Lightjet print

98 x 154 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.32. Image courtesy of the artist.

Whether altering the nature of an architectural space or, as in the case of Café Extra-Forte (2011) from the series Fundos, creating a two-dimensional image to hang on the wall, Lucia Koch reorients, skews, or reframes perception. Koch transforms the sense of place by drawing attention to architectural features and qualities wherever she finds them; some are intrinsic to a built environment and others are hidden within an ordinary object. Here Koch brings together the historically honored painting technique of trompe l’oeil with photography, the medium of purported “truthfulness,” to destabilize a viewer’s sense of where she is and what she is looking at. Without an internal point of comparison it is impossible to know the size of the volume carved out in this picture, but it certainly feels monumental.

Experiments with size have been critical to the evolution of contemporary photography. Photographers Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, and Candida Höfer are known for leveraging scale to various effects and can be studied to contextualize Koch’s work: Struth uses a large format that maximizes detail to simultaneously clarify and disorient, Ruff engages scale to dimensionalize manipulated images, and Höfer employs it to imitate the grand spaces she depicts. Koch’s unique approach integrates elements of each to create something new and expansive. All of her manipulations take place within the viewfinder, and the overwhelming clarity of her photographs as well as the size at which they are experienced at first mystify viewers, before providing “Aha!” moments. Despite their suggestions of something else, Koch’s images are actually documents of everyday objects.

When viewers approach the monumental Café Extra-Forte (2011), it is as if they were about to enter a new room, yet one that strikes a memory. Here, Koch poetically reframes and, in this case, enlarges the foil interior of a familiar package––the coffee bag. In highlighting the item’s structure and removing its surrounding context, she transforms packaging into architecture, creating a space for heightened awareness and reflection. Whether we are subsumed by the visual depth she creates or connected to our own depths of feeling, Koch is using her lens to help us use ours.

--Maria C. Taft

Kiki Kogelnik

(Austrian, b. 1935)Red Eyed, 1997

Oil and acrylic on canvas

72 3/32 x 53 63/64 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.6.30. Image courtesy of König Galerie, Berlin/London, and Kiki Kogelnik Foundation, Vienna and New York.

Joseph Kosuth

(American, b. 1945)No Number 3 [warm white, large version], 1991

Warm white neon

5 1/2 x 102 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.100. © Joseph Kosuth. Image courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, New York.

The 1960s witnessed a radical reconsideration of many social, political, and cultural conventions, and the field of fine art was no exception. Joseph Kosuth launched an inquiry into the very nature of art itself, which he mounted alongside other artists, including Lawrence Weiner and Mel Bochner, who are also in The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art at Rollins College. Together, these individuals pioneered the Conceptual art genre that emerged during the second half of the decade and reached its apex in the early 1970s. Kosuth and his contemporaries rejected Modernism’s emphasis on aesthetics, formalism, and self-expression, arguing that the sole defining feature of a work of art is not its physical makeup, but the idea behind it. Kosuth put forward this theory in one the most important treatises on Conceptual art, Art After Philosophy, published in 1969, the same year he became the American editor of the journal Art & Language. Nevertheless, his artworks are the most concise examples of his philosophy.

No Number 3 [warm white, large version] (1991) exhibits many of the properties that define Kosuth’s practice in particular and Conceptual art more generally. Comprised simply of the phrase “Language Must Speak for Itself” written in warm white neon letters, the artist relies exclusively on text to discourage the type of aesthetic contemplation that images normally invite. In other words, Kosuth turns the viewer into a reader, making the statement “Language Must Speak for Itself” more significant than the visual appearance of the neon tubing with which it is written. This work demonstrates Kosuth’s own conviction that a work of art’s physical manifestation is secondary to its concept. For example, although the piece was fabricated in 2013, it is dated 1991, the year that it was conceived alongside a blue version of the piece in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. The fact that Kosuth privileges the date that he came up with the idea for the piece shows that a work of art can exist as an intangible, independent idea apart from its material form.

--Sarah Parrish

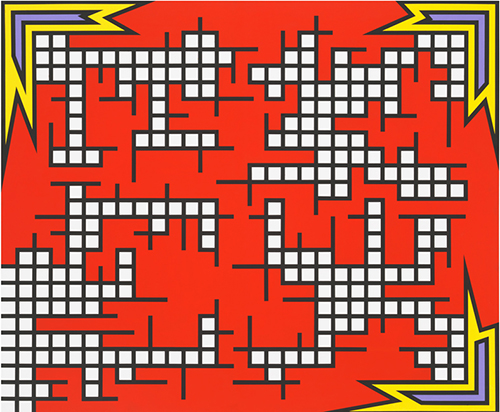

Nicholas Krushenick

(American, 1929-1999)Wire Mill Road, 1972

Acrylic on canvas

50 x 60 x 2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2015.1.38. Image courtesy of the Estate of Nicholas Krushenick and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

Bronx native Nicholas Krushenick, like many artists of his generation, studied at both the Art Students League and the Hans Hofmann School of Art. Also like other painters of his generation, Krushenick sought a way out of the gravity well created by Abstract Expressionists like Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. Inspired by the luminous late works of Henri Matisse, he began developing his own version of abstract painting, eventually settling on a hard-edged style that blended the allover composition of Abstract Expressionism with the black lines and bright colors of Pop. Though his use of black line is often compared to that of Roy Lichtenstein, Krushenick had begun experimenting with the device—which he got from his study of the work of the Cubist painter Fernand Léger—before becoming aware of Lichtenstein’s work. Krushenick’s experiments in these directions have led him to be credited with pioneering the style now known as Pop Abstraction.

Wire Mill Road is a fine example of the direction his work took in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when he began replacing his earlier interest in sharply rendered yet still biomorphic forms with a closer adherence to the grid. Its rich, luminous colors are the result of Krushenick’s devotion to Liquitex acrylic paints, which he was one of the first New York artists to adopt upon their introduction in 1955. He loved acrylics for their bright, even psychedelic, colors, and the way in which they retain their purity upon application. This purity stands in contrast to oil paints, which he considered muddy. Krushenick would continue his experiments with bright, sharp form until his death in 1999, though he pulled away from the New York art world in the late 1970s, instead devoting himself to teaching. Krushenick was a professor at the University of Maryland from 1977 to 1991, and also occasionally taught as a visiting professor at other institutions.

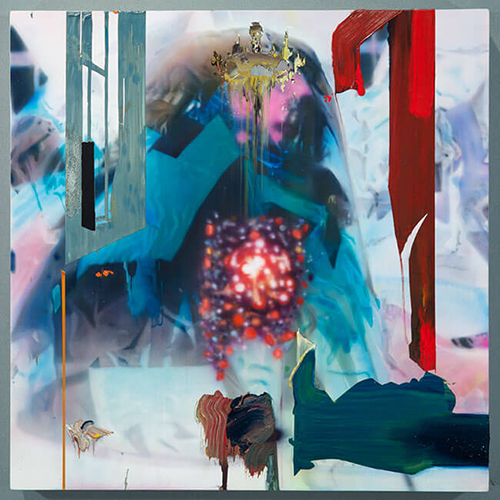

Tom LaDuke

(American, b. 1963)Mirror Drive, 2013

Oil and acrylic on canvas over panel

20 x 20 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.21. Image courtesy of the artist and CRG Gallery, New York. Photo credit: Susan Alzner, New York.

In the paintings of Tom LaDuke, image, time, and memory are compressed to create works that—much like Alice in Wonderland—draw the viewer into thrilling and disorienting spaces.

LaDuke, who also makes sculptures of material invention, draws upon a vast art-historical, filmic, and personal image bank when conceptualizing his canvases. Treating layers of information with varying effects, LaDuke in essence merges superimposed, photorealistic, brushless backgrounds and mid-layers with overlayers of impasto-like passages that are cut like topographical data—completely abstracted at one level, but also the key to the iconography hidden inside the painting.

The effect can be like looking at analog film that has been double-exposed and then left in the rain. One can pick out a distinct element of each layer, but it is the dizzying new whole that confounds and astounds.

In many works, an iconic film serves as the first stratum of information, followed by the autobiographical/voyeuristic image of his studio with the work in progress, and finally, fragments of an art-historical painting rendered in fleeting, poetic fragments — for instance, the mysterious unidentified orb in Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533) in LaDuke’s painting Blade Runner [1982] (2001) or, in the case of Mirror Drive (2013), the swath of the red canopy from Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434). The presence of the artist in his paintings is not created by any identifiable brushwork, but by the flat, hyperreal treatment of personal content—in this case the debris outside his studio and the talismanic material of his mother’s blouse.

When a film is the source of a LaDuke image, the scale of the painting often reflects the oversized proportions of the screen. However, in Mirror Drive (2013), LaDuke has downshifted to make a painting that echoes the likely scale of the slightly convex mirror pictured in van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait. The viewer, instead of feeling engulfed by the image as in a theater, searches for herself, much like she would in the mirrored glass of Arnolfini. So too, just as van Eyck depicted himself in its reflection, LaDuke presents himself through the objects he uses as his foils.

Through the merging of this information, LaDuke invites the viewer into the experience of the painting—material, visual, and emotional—and with a delicate compass, sets her free to find her own way.

--Abigail Ross Goodman

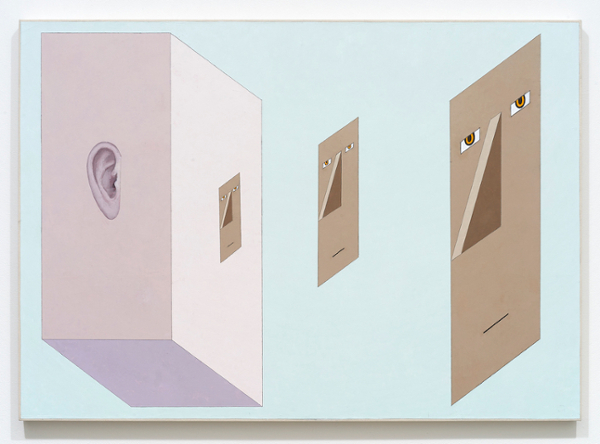

Mernet Larsen

(American, b. 1940)Conversation, 2012

Acrylic and tracing paper on canvas

35 3/8 x 49 3/4 x 1 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2018.1.32. © Mernet Larsen. Image courtesy of James Cohan, New York

Mernet Larsen

(American, b. 1940)Skydiver (after El Lissitzky), 2016

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

65 x 53 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.1. © Mernet Larsen. Image courtesy of James Cohan, New York

Jonathan Lasker

(American, b. 1948)Reasonable Assembly, 2003

Oil on linen

60 x 80 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2021.1.29 © Jonathan Lasker

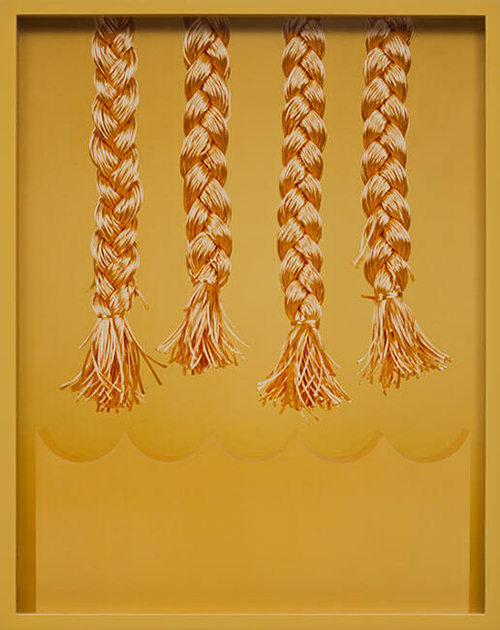

Elad Lassry

(Israeli, b. 1977)Four Braids (Yellow), 2012

C-print with painted frame

14 1/2 x 11 1/2 x 1 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.22. Image courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

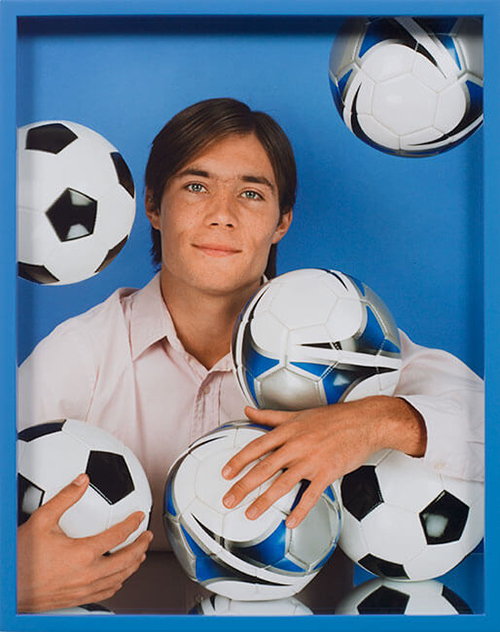

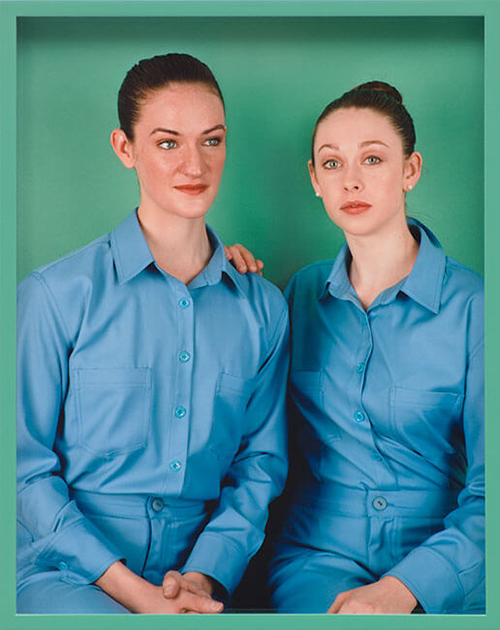

Elad Lassry has leveraged a variety of media (photography, film, sculpture, performance) to engage the history of the image and challenge viewers’ expectations of pictures in subtle but powerful ways.

Old magazines, advertisements, and other commercial image sources, many from the 1970s and ’80s, inspire his photographic works. His depictions of generic subjects—from conventionally attractive people to bric-a-brac—are always slightly puzzling. Shot straight-on with crisp, centrally balanced compositions, solid backgrounds, and repeated elements, his works can at first be off-putting as he reveals and exaggerates the oddities of commercial visual language. In addition to producing highly stylized studio shots, Lassry also frequently co-opts existing images—like vintage Hollywood headshots—and changes their context through gestures of cropping and framing. All these works are printed roughly the size of a magazine page, a scale viewers know intuitively, and are set in a highly specific frame.

The now signature “Lassry” frames, each color matched to the image enshrined, serve an integral, as opposed to a supporting, role in his work. When taken together—image and frame—the works transcend the practice of photography to exist in the world as sculptural objects.

Working this way, Lassry represents the next era in the appropriation photography pioneered by The Pictures Generation. Richard Prince’s “rephotography” began in the mid-1970s. Prince photographed advertisements, favoring iconic figures such as the Marlboro Man. Through cropping and enlarging he played with authorship and critiqued photography’s innate lack of originality. Soon after, sculptor Haim Steinbach began arranging commercially available objects—from toys to trash cans—on custom shelves, highlighting how the relationship between objects changes their meaning.

With Lassry, individual images are exhibited in ways that are meant to further guide the viewer’s experience. Sight lines are cropped or revealed through architectural half-walls and apertures or interior windows, as the artist attempts to play with our access to the images. Through such repetition, composition, and presentation, Lassry draws attention to the construction of contemporary images, which are rendered invisible by their ubiquity. It is the viewer’s perception that Lassry is challenging and reanimating.

--Al Miner

Elad Lassry

(Israeli, b. 1977)Ginori (Yellow), 2011

C-print with painted frame

11 1/2 x 14 1/2 x 1 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.24. Image courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Elad Lassry

(Israeli, b. 1977)Man (Soccer Balls), 2012

C-print with painted frame

14 1/2 x 11 1/2 x 1 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.25. Image courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

Elad Lassry

(Israeli, b. 1977)Women (055, 065), 2012

C-print with painted frame

14 1/2 x 11 1/2 x 1 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.23. Image courtesy of the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

In the work Lassry generically titled Women (055, 065) (2012), he poses two seated women in identical nondescript outfits. The nearly unnatural green color of their eyes matches the background and frame. Though his models are often friends and collaborators, he uses them as props of equal value to the objects he depicts; they are all isolated and awkward. These women appear often in his oeuvre, most recently as the subjects of his 2012 High Line commission, similarly titled Women (065, 055.)

--Al Miner

Brandon Lattu

(American, b. 1970)Boy with Image of Payphone, 2016

Inkjet print, aluminum frame

55 x 40 x 2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2017.6.31. © Brandon Lattu. © Brandon Lattu. Image courtesy of Koening & Clinton, New York. Photography: Jeffrey Sturges, New York

An-My Lê

(Vietnamese, b. 1960)29 Palms: Force Recon, 2003–2004

Silver gelatin print

26 1/2 x 38 x 1 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.84. Image courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York.

An-My Lê is a contemporary photographer who primarily focuses on documenting the experiences and landscapes of war. Unlike the photojournalist, who instantly captures the combat and action of war, Lê uses a large format camera to take richly detailed and classically framed photographs that record war's rehearsals and memories. Her work portrays a different set of temporalities—anticipation, waiting, and recollection—and intertwines the real and the imagined.

Her series, 29 Palms: Force Recon (2003-2004), documented military training at a virtual “Middle East” erected in the California desert. In the arid landscape, amid a series of structures built to resemble neighborhoods in Iraq and Afghanistan, soldiers trained for future combat missions in distant lands. Her picturesque compositions of the enacted war scenes highlight their constructed nature and generate a contemplative, critical distance from the acts of war. By exploring displacements in space and time — whether 1970s Vietnam in the contemporary South or the Middle East outside of Los Angeles — Lê expresses her personal experiences, which have been dramatically shaped by the processes of war. [1] Her photography signals the multitude of ways that the real and the imagined merge in the acts and memories of wars.

[1]Rooted in histories of artistic appropriation and performance, the re-enactment has emerged as a key cultural form of the 21st century, used by artists for two common critical purposes: to “rewrite” history by offering a forum for other viewpoints traditionally kept outside the “grand narratives” and to deconstruct the images and accounts that have comprised these narratives. For more on re-enactments, see Robert Blackson, “Once More . . . With Feeling: Reenactment in Contemporary Art and Culture,” Art Journal 66: 1 (Spring 2007): 28-40.

An-My Lê

(Vietnamese, b. 1960)Small Wars (Rescue), 1999–2002

Silver gelatin print

26 1/2 x 38 x 1 1/2

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.85. Image courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York.

Her next two photographic projects drew more explicitly on imagination and displacement, specifically as they operate in re-enactments and pre-enactments. Her Small Wars series (1999-2002) centered on Vietnam War re-enactors in North Carolina and Virginia, who carefully re-stage the daily life and battles of soldiers. Lê photographed these re-enactments over two summers. As a condition of access, her participation was required, and she was cast as a Viet Cong captured by American GIs.

An-My Lê

(Vietnamese, b. 1960)Untitled, Gai Lai, 1994

Silver gelatin print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.87. Image courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York.

Though born in Saigon, Lê immigrated to the United States as a political refugee in 1975, the last year of the Vietnam War. Her own displacement from Vietnam, as well as her trove of personal memories layered upon popular representations of her former home, inspired her first major photographic project, Untitled (Vietnam) (1994-1998). For this body of work, Lê traveled back to Vietnam and documented the contemporary landscape. Her immaculate and spare photographs of crumbling buildings, a burning field, or a boy aiming a slingshot skyward invite myriad and oblique references to war. In Untitled, Gia Lai (1994), toy airplanes attached to long sticks and hoisted above a roof like television antennae seem to mime wartime air strikes or perhaps serve as a protective talisman against such attacks. Lê's series documents and envisages the traces of war in their physical, social, and psychic dimensions.

An-My Lê

(Vietnamese, b. 1960)Untitled, Ho Chi Minh City, 1995

Silver gelatin print

20 x 24 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.86. Image courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York.

Susie J. Lee

(American, b. 1972)The Fracking Fields: Atom, 2013

High-definition video portrait

20 minutes 35 seconds

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2021.1.11 © Susie J. Lee

Susie J. Lee

(American, b. 1972)The Fracking Fields: Atom, 2013

High-definition video portrait

20 minutes 35 seconds

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2021.1.11 © Susie J. Lee

Maya Lin

(American, b. 1959)Silver Thames, 2012

Recycled silver

19 x 78 x 1/2 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2013.34.88. © Maya Lin Studio. © Maya Lin Studio. Image courtesy of Pace Gallery

If we had a God’s-eye view of our world, would it affect our actions? Would we make different choices if we could see the interconnectedness of our waterways and oceans? Would we reconsider our wasteful habits? Maya Lin’s elemental and elegant recycled silver works prod us to pose these questions.

Lin has brought her thought and memorializing sensibility to the subject of the world’s waterways. In wall-mounted reliefs that harken back to the clarity of form of vintage silhouette portraits, Lin traces the path and volume of some of the world’s essential rivers and casts them in recycled silver. The material, chosen for its preciousness and reflective quality, enables the final works that live directly and discretely on the wall to radiate, and imbues them with an almost mystical quality. The shapes of each of these recycled silver works—as distinct and familiar as their waterway subjects—are our lifelines. They are the true sources of our wellbeing, community, and industry, and are visually kindred to the unique creases of our hands. In Silver Thames (2012) we see the meandering path of the river as it stretches from Gloucestershire through London to the Thames Estuary by Southend-on-Sea. Generations ago, the nuances of the whole would have been known by its inhabitants, but such awareness has been replaced by a micro-view. Lin is encouraging us to reawaken our vision and recognize these bodies of water as the great providers that they are. It is difficult to care for something we cannot see, so Lin gives us vision. She reminds us of the rivers’ beauty and fragility, and of our responsibility to revitalize these places that have been weakened, if not altogether destroyed, as consequences of human and industrial negligence.

Lin’s artistic practice is highly aesthetic but also profoundly conscientious, and she purposefully accepts her role as an agent of change. In these works and other related series of pin rivers, cut marble topologies of vanishing bodies of water, and her multi-part memorial What Is Missing, Lin realizes her power as an artist to bring attention to what is at stake. Her sculptures are at once elegies for what was, but also celebrations of what could be again. She is using her art to call for change and to inspire action, restoration, and hope.

--Abigail Ross Goodman

Daniel Lind-Ramos

(Puerto Rican, b. 1953)Vencedor: 1797 (Victorius: 1797), 2018-2019

Mixed media

67 x 70 x 33 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.1 ©Daniel Lind-Ramos

Cultural memory, history, identity, resiliency, and community are core themes in Daniel Lind-Ramos' artistic practice. Created with discarded materials and everyday objects collected from his hometown of Loíza, Puerto Rico, his assemblages incorporate references to the area’s Afro-Caribbean heritage, the experience of his community, and the nuanced history of colonialism. This work celebrates the victory over the British navy in the Battle of San Juan in 1797 when a fleet led by Sir Ralph Abercromby assaulted the island to seize it from Spain. Local black militias in Loíza played a crucial role in the defeat of the British, a fact that is often overlooked in accounts of the event. Vencedor 1797 is a reminder of the resiliency of the Puerto Rican people when faced with adversity and speaks to the lasting effects of colonialism in the Caribbean. Various elements in the sculpture allude to Afro-Caribbean religions, manual labor, community, the land, and even local sports.

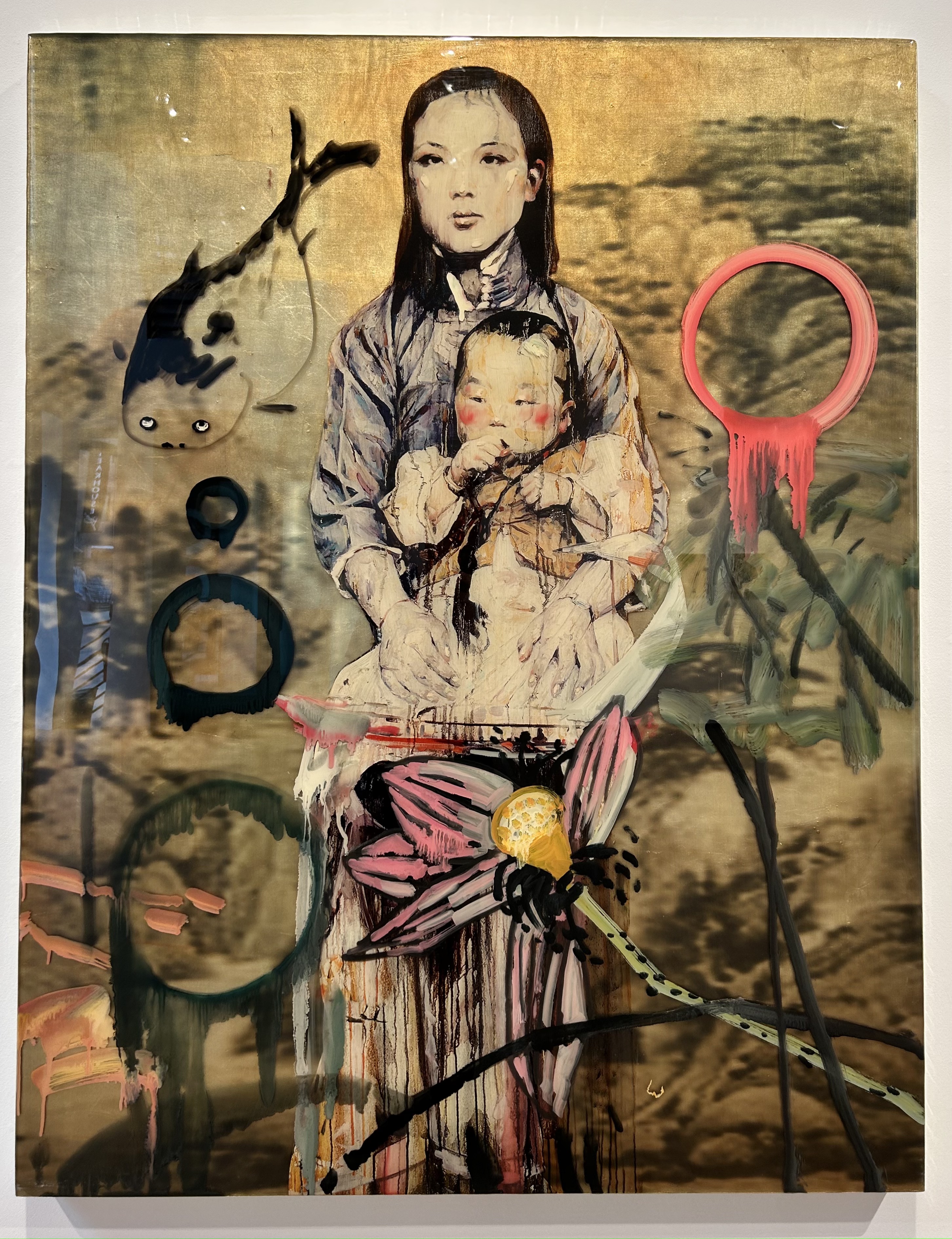

Hung Liu

(Chinese, 1948 – 2021)Madonna, 2008

Resin and mixed media

52 X 41 In.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ‘68 Alfond, 2023.1.17 © 2023 Hung Liu Estate. Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In Madonna, Hung Liu depicts a young woman with a baby on her lap against a monochromatic background. Liu includes symbols rooted in Buddhist iconography, such as black and pink circles to suggest themes of wholeness and enlightenment. Similarly, the outlines of a koi fish and a pink flower represent hope. Born in Communist China in 1948, Liu grew up in Beijing, and was later relocated to a rural village for "re-education" as part of the Cultural Revolution. She worked on a farm and began drawing people she befriended. When Liu returned to Beijing she pursued higher education in art, and later moved to California where she attended the University of San Diego. Her expressionist style flourished in this context. Photographs of women, workers, and other stereotyped groups inspired Liu, and her practice honors these anonymous figures: "I hope to wash subjects of their 'otherness' and reveal them as dignified."

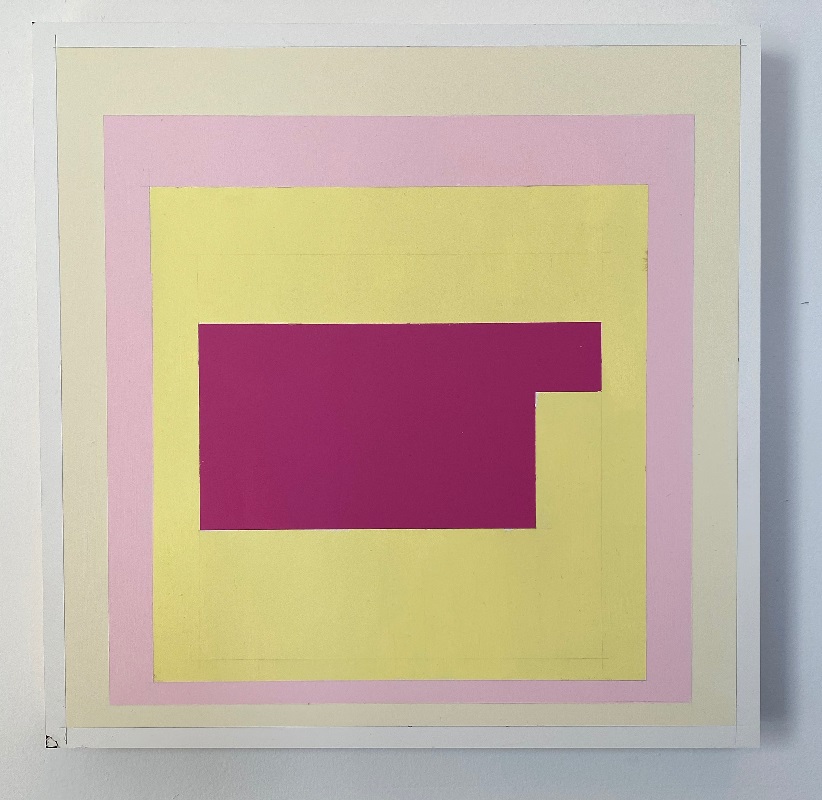

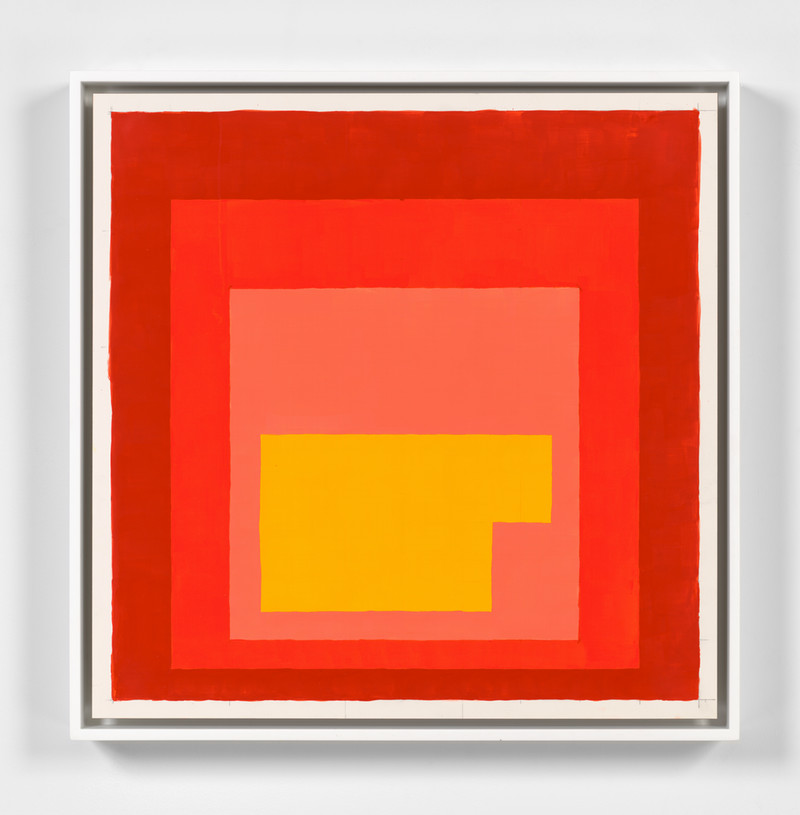

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Homage to the Auction Block #10, 2019

Gouache on panel

16 x 16 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.14 © Steve Locke

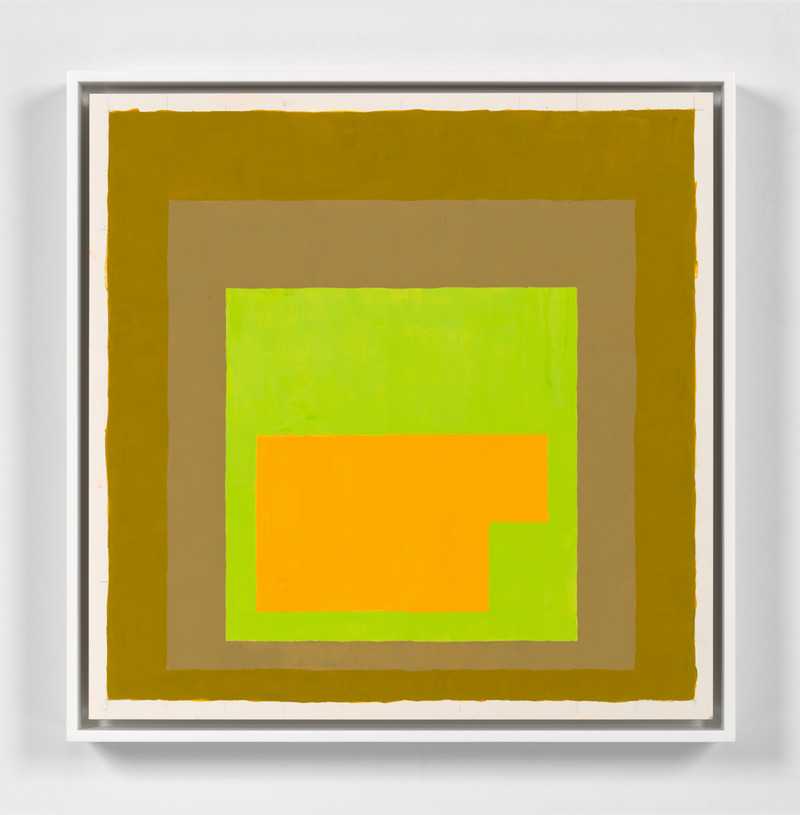

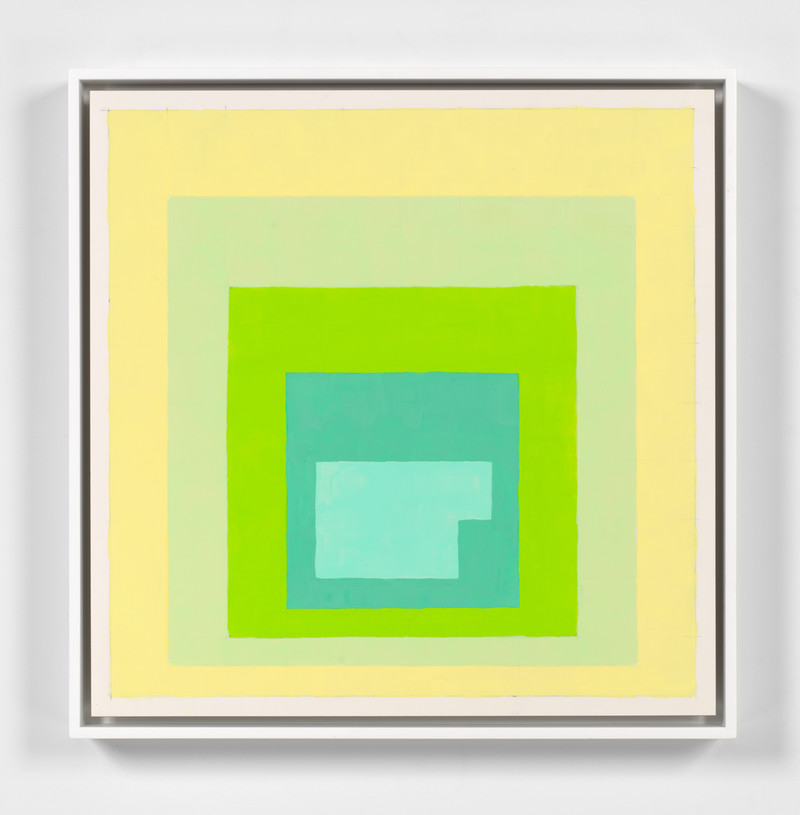

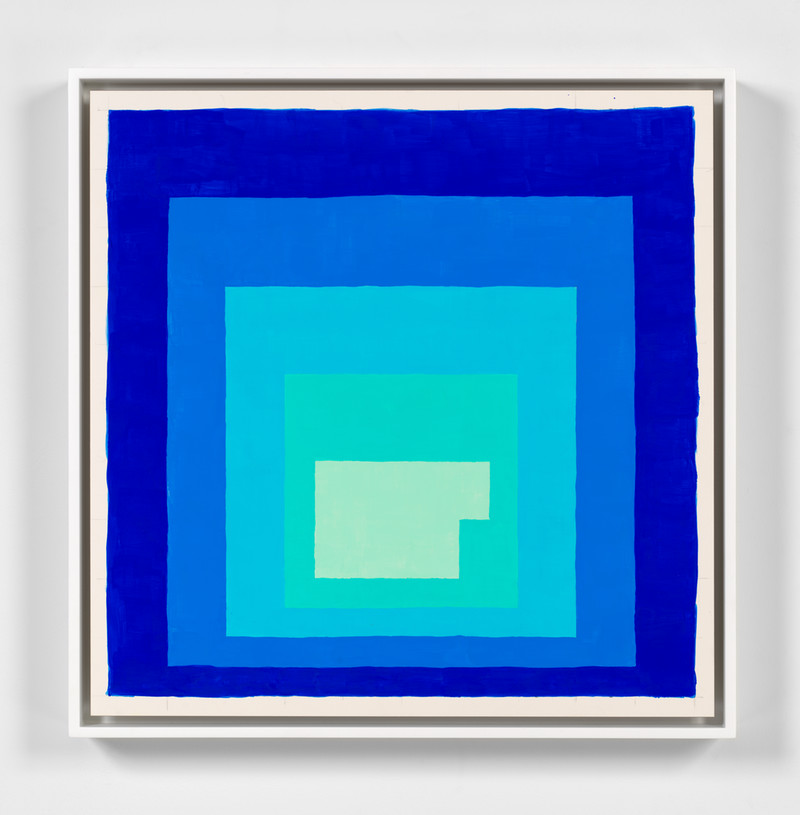

Steve Locke probes perceptions of race, memory and male identity through his multi-disciplinary practice. Coming out of his proposed, but ultimately unrealized Auction Block Memorial, which sought to recognize the Africans and African Americans whose trafficking and sale financed the building of Boston’s Faneuil Hall, Locke’s Homage to the Auction Block is both a tribute to, and a subversion of, Homage to a Square: Josef Albers’ famous investigation of the interactions of color and form through the nesting of squares of pigment. For this project, Locke inserts the rectangular form of the “auction block” motif, a powerful symbol of chattel slavery in the Americas, into each composition. As with Albers’ work, the application of color and the use of the grid are reliant on the tenets of modernist abstraction, but the ever-present form of the auction block centered in seas of rich, vibrant color is a constant reminder and poignant critique of slavery’s dark and persistent history. Locke lives and works in New York.

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Homage to the Auction Block #11, 2019

Gouache on panel

16 x 16 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.15 © Steve Locke

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Homage to the Auction Block #12, 2019

Gouache on panel

16 x 16 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2020.1.16 © Steve Locke

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Untitled (I Remember Everything You Taught Me Here), 2020

Neon

42 x 115 ¼ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond. 2021.1.13 © Steve Locke

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Rollins Suite #1a-this place, 2021

Acrylic on Claybord

17 x 17 x 2 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.1 © Steve Locke/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Rollins Suite #1b-the place before, 2021

Acrylic on Claybord

17 x 17 x 2 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.2 © Steve Locke/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Rollins Suite #2a-the place i am, 2021

Acrylic on Claybord

17 x 17 x 2 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.3 © Steve Locke/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Rollins Suite #2b-the place i recall, 2021

Acrylic on Claybord

17 x 17 x 2 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.4 © Steve Locke/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Rollins Suite #3a-the place i lost, 2021

Acrylic on Claybord

17 x 17 x 2 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.5 © Steve Locke/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Steve Locke

(American, b. 1963)Rollins Suite #3b-the place i discovered, 2021

Acrylic on Claybord

17 x 17 x 2 1/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2023.1.6 © Steve Locke/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

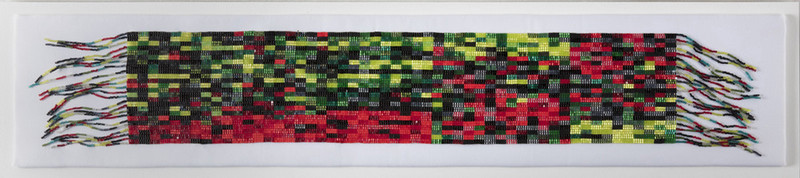

Erica Lord

(Athabascan/Iñupiat, b. 1978)Adrenocortical Cancer (Diabetes Complication), DNA Microarray Analysis, 2021

Beads and string

49 x 7 ½ in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2023.1.7, Courtesy of the Artist Ave Accola Griefen Fine Art. Photo by Addition Doty

Referencing the computer-generated patterns drawn from DNA analysis, Erica Lord’s colorful loom-weaving comments on health disparities experienced among Native populations. Lord’s work takes the form of a customary burden strap—a tool used by indigenous women to carry heavy objects or children —to represent the emotional weight of illness. The pattern references adrenocortical cancer, which has been linked to diabetes, one of the many illnesses that disproportionately affects this community. From her series The Codes We Carry, Lord's weaving engages with traditional Native American beadwork practices to reflect the invisible burdens this population carries.

Born in Nenana, Alaska, to a Finnish American mother and an Athabascan/Iñupiat father, Erica Lord is an interdisciplinary artist whose mixed heritage allows her to explore her identity and its overlapping cultural borders. Informed by her background, Lord’s artwork showcases themes of displacement, cultural limbo, and health inequities.

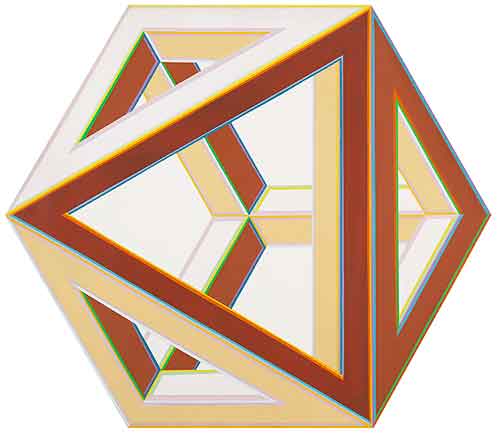

Al Loving

(American, 1935-2005)Untitled, 1969

Acrylic on canvas

40 x 35 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Gift of Barbara '68 and Theodore '68 Alfond, 2016.3.14. Image courtesy the Estate of Al Loving and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

After earning his MFA from the University of Michigan, Al Loving spent a few years teaching before moving to New York City in 1968. Almost immediately upon his arrival he became the first African American artist to receive a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This work was one of six shown at the exhibition, which was titled Alvin Loving: Paintings and ran from December 1969 to January 1970. Loving at the time was influenced by his mentor from Michigan, Al Mullen, who had trained with the famed teacher Hans Hofmann in New York. Along with a number of other painters of the 1960s and early 1970s, Loving was interested in creating and exploring complex juxtapositions of color, structure, and space, in essence creating a new formal language with his carefully composed, hard-edged paintings.

Loving—along with other Black abstractionists—came under harsh criticism by Black cultural activists for the resolutely apolitical nature of his work, which seemed not to speak to the realities of Black life in America. Dismayed by this criticism, Loving—who was a committed Civil Rights and antiracist activist—began to rethink his commitment to hard-edged painting. Inspired by the work of Romare Bearden, African American quiltmakers, his work as a dancer with the Batya Zamir Dance Company, and his love of jazz, Loving eventually renounced work in this style, instead dying and cutting strips of canvas which he sewed together in complex, quasi-improvisational compositions. Despite this shift in his style—and his later professed distaste for works such as this one—scholars have noted the affinities between works like this and his later, improvisational works, in particular the concern with complex formal structures and the contingent relationships between colors.

Rita Lundqvist

(Swedish, b. 1953)Puddle/Pöl, 2017

Oil on panel

15 3/4 x 15 3/4 in.

The Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Rollins Museum of Art. Gift of Barbara ’68 and Theodore ’68 Alfond, 2022.2.3. Image courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

Known for her quiet compositions inhabited by abstract figures, Swedish figurative painter Rita Lundqvist challenges notions of storytelling through her painting practice. Coming of age in the 1970s, Lundqvist was influenced by the growing conceptual and land art movements. Her works have remained consistent in scale and perspective, and often her color palette references classical Nordic landscape paintings. In this work, the sparse environment brings attention to a simplified tree and a small puddle near the feet of a blonde figure. She looks outward to the viewer, although it is unclear if she intends to address them. While neither the same figure, nor a coherent story, ever emerges across her oeuvre, Lundqvist says that recurring motifs of person and object connect her paintings. This lack of narrative intentionally allows space for the viewer to create the story of the scene using their own associations and experiences.

![No Number 3 [warm white, large version]](images/artists-ko/kosuth-joseph-no-number-3-thumb.jpg)