Photography

Artists Featured in This Section

| Dawoud Bey | Margaret Bourke-White |

| Mathew M. Brady | Brassaï |

| Imogen Cunningham | Edward Sheriff Curtis |

| F. Holland Day | William Henry Jackson |

| Gertrude Käsebier | Edward Steichen |

| Alfred Stieglitz | Paul Strand |

Dawoud Bey

(American, b. 1953)Janice Kemp and Triniti Williams, 2012

Archival pigment prints mounted on dibond

40 x 64 in (40 x 32 in individually)

Museum purchase from the Kenneth Curry Acquisition Fund, 2015.9., Image courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery

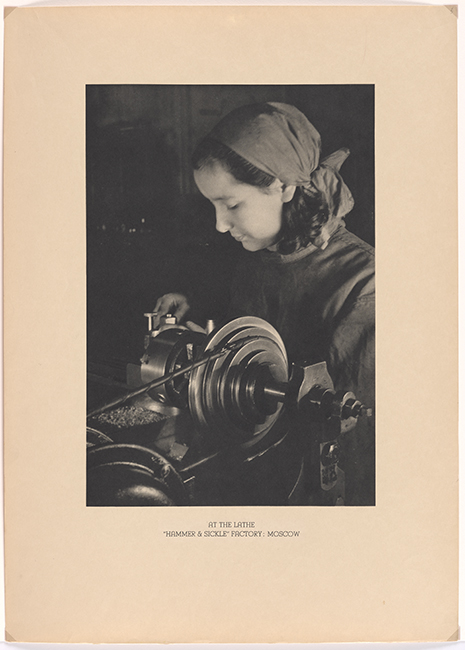

Margaret Bourke-White

(American, 1904-1971)At the Lathe "Hammer & Sickle" Factory: Moscow, 1931

Photogravure print

20 ¼ x 16 ¼ in.

Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund, 2013.22 © 2023 Estate of Margaret Bourke-White / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Mathew M. Brady

(American, 1823–1896)Abraham Lincoln, 1861

Albumen print from wet collodion negative

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.9

The first photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken by the Mathew Brady Studio, by Brady himself or one of his camera operators, was on February 27, 1860, on the day of Lincoln’s address to a large Republican audience in the modern lecture hall at Cooper Union in New York City. The three-quarter view shows Lincoln, standing next to a classical column with his left hand resting on two leather-bound books. His clean-shaven appearance exposes distinctly high cheek bones. For the general public, the image was available and collected as carte-de-visite photographs. During the year, artists reproduced the photograph as wood-cut engravings, published in Harper’s and Leslie’s Illustrated. The public access to this visual image of Lincoln is credited with getting the Illinois politician elected as the 16th President of the United States.

The Lincoln portrait in the Cornell Fine Arts Museum’s collection, also a carte de visite photograph, corresponds to one at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. The nearly full-length portrait of Lincoln with full beard and long hair, dressed in suit and tie with a visible watch chain displays him in his early presidency—a dignified, reserved, and youthful appearance. The Brady studio utilized as formal props—drapery in front of a column, the base still visible on the left and on the right a chair with three spindles.

According to the National Portrait Gallery’s evidence—a soldier’s diary—the photograph was taken on April 17, 1863 by Thomas Le Mere at the Brady Studio in Washington. Although, Lincoln appeared for a studio portrait sitting on that date, more recent evidence by historians Dr. Thomas Schwartz and Dr. James Cornelius, curator of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, point to an earlier dating.

Schwartz’s article “A Mystery Solved: Arthur Lumley’s Sketch of Abraham Lincoln” published in the Journal of Illinois History (2003) links Lumley’s drawing made on May 16, 1861 in the Brady Washington Studio to photographs of Lincoln made on that day. Schwartz points out that the drawing is consistent in appearance with several photographs showing the President with the spindle-back chair prop. Correspondingly, Cornelius cites several personal and political circumstances, which Lincoln experienced following this date that would have caused him to adopt a more serious, less relaxed expression than that visible in this image.

Brassaï

(Hungarian, 1899–1984)Henri Matisse Drawing from the Nude, 1939

Photogravure

Purchased with funds from the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.30

Brassaï, the pseudonym of Gyulas Halász, made his name in photography with the publication of Paris by Night 1933, an intimate and sympathetic documentation of night life in the humbler quarters of Paris. Brassaï was mesmerized by the city’s activity during the evening hours. Fellow Hungarian and photographer André Kertész loaned him a camera and suggested he document the nocturnal life of the bars, brothels, mirror-lined cafes and dance halls and on the streets.

As a former painting student transplanted to Paris in 1923, Brassaï became friends with many of the avant-garde painters in the city. In early June of 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, and at the request of Henri Matisse, Brassaï carried out a series of photographic “Nudes in the Studio” of the artist drawing his model at Villa d’ Alésia in Paris, at the studio lent to him by American sculptor Mary Callery. The staged photograph was one of several at this sitting used as illustrations for Brassaï’s book The Artists in My Life. The model, nude except for bracelets and slippers, poses in various locations within the studio as Matisse dressed in professional attire draws from life. Brassaï noted of these photographs, “Standing in his bright, light flooded studio in his white smock, Matisse looked like the chief of staff in some hospital. Oddly, enough, he had had the same appearance as a young man…his fellow students at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts had nicknamed him “The Doctor.”

Brassaï’s acquaintance with Harper’s Bazaar editor Carmel Snow and art director Alexey Brodovitch, and as a colleague in Parisian artistic circles granted him opportunities to photograph many artists for the magazine. For more than thirty years, he documented among them, Bonnard, Giacometti, Braque, and Le Corbusier, in their homes in Paris, Normandy, and elsewhere during various periods of their lives.

Imogen Cunningham

(American, 1883–1976)Pentimento, 1973

Photographic print

17 1/4 x 14 1/4 in.

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.14

The first time Imogen Cunningham photographed the transcendental painter Morris Graves was in 1950 on the grounds of his private retreat outside Seattle. An introspective portrait study of Graves who as a conscientious-objector had refused to enter the military during World War II resulted in his imprisonment, Cunningham’s photograph is considered a classic portrait. The photographer commented about the image, “Many people think it’s the only portrait I’ve made. You know, he’s never said whether he like it or not.”

Nearly twenty years later, in 1969, Cunningham sought out the reclusive Graves to include him in her venture After Ninety, a project about old age. He turned her down. She was persistent and several years later, in 1973, he agreed to have her photograph him, musing, “How can anyone refuse a 90-year old like Imogen anything?” Cunningham was 90 and Graves 63.

As a college student, Imogen studied chemistry and worked in the botany department of the University of Washington. She became interested in photography in 1905 working with a 4 x 5 camera ordered through a mail-order correspondence school. Gertrude Käsebier’s 1907 article published in The Craftsman inspired her. Cunningham worked in the Seattle studio of Edward S. Curtis, a chronicler of Amerindians, for two years beginning in 1907, learning the fine points of platinum printing and retouching of negatives. Following a fellowship to Dresden, Germany where she studied with a photo chemist, viewed the International Photographic Exhibition and artwork at museums, she opened a portrait studio in 1910 upon her return to Seattle.

Throughout her career that spanned 70 years Cunningham featured portraiture and images of the body including nudes, however she is most well known for the photographs emanating from her affiliation with the California formalists group F/64 that included photographers Edward Weston and Ansel Adams. The name derived from the f-stop on the camera that provided the sharpest focus and depth of field. Inspired by these associations Cunningham developed her early style—close-ups photographs of industrial complexes, botanical plants and flowers—calla lilies and magnolias blossoms. Ten of these photographic studies debuted in the exhibition Film und Foto featuring works by American and European artists held in Stuttgart, Germany in 1929.

F. Holland Day

American, 1864–1933Ziletta, 1895

Photogravure print

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.12

F. Holland Day’s portraiture titled Zilleta depicts a young unidentified woman posing as the mythical figure of the same name. Less concerned with the representation of an individual and more interested in expressing ideas of spirituality, the photographer’s study is meant to convey a feeling rather than be a document of fact. At this point in his artistic career, Day was deeply involved in the study of manifold religious beliefs; and had became an avid collector of Catholic artifacts.

Further having grown up in a wealthy Massachusetts family and been indoctrinated in the era’s progressive ideals, Day was sympathetic to people who were disadvantaged—immigrants, people of color, and the poor, whose lives were less fortunate than his. He became an instructor of photography at a settlement house in the North End of Boston. In the late 1890s, he began to use ethnic and African-American models for his photographic studies.

Costumed wearing large hoop earrings and her hair covered in a cloth headpiece, Day’s model projects ethnic origins. Her face cast in shadow evokes a mysterious and exotic quality. The model for Zilleta appears as The Novice, ca. 1896 and several other photographs in the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Louise Imogen Guiney Collection. That Day used the same model in several studies signifying her appearance suitable for his exploration of a wide range of spiritualistic and emotional expressions and experiences.

Day began photographing around 1887. Co-founder of the Boston publishing firm Copeland & Day which published Oscar Wilde’s Salome and the Yellow Book by Aubrey Beardsley, he gave up book publishing to pursue photography as a fine art form. His narrative photographs explore allegorical, legendary, and biblical themes. His best-known work is a series of 250 photographs recreating the last days of Christ.

Active in the Pictorialist movement in the U.S. and Europe, he was a member of Britain’s exclusive photographic association the Linked Ring Brotherhood; however, he declined an invitation to join Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession group. In 1900, Day organized an extraordinary exhibition of American art photographers 400 works collectively titled the New School of American Photography in London and Paris.

William Henry Jackson

(American, 1843–1942)Quandary Peak, Blue River Range in Distance, North from the Summit of Mt. Lincoln, 1873

Albumen print from wet collodion negative

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.10

Between 1870 and 1878 William Henry Jackson was an official photographer for the U.S. Geological Survey under the directive of Ferdinand V. Hayden. Jackson’s photographs of the natural wonders of northwestern Wyoming taken during 1871 were presented to members of Congress who voted in 1872 to establish Yellowstone National Park and Grand Teton National Park, and by 1874, the cliff dwellings of Colorado were designated Mesa Verde National Park. His tour de force became his panoramic views composed of anywhere from 2-6 plates. Most of the panoramas were designed so that at least half of the views could be sold as satisfactory, even dramatic single-plate images.

In July 1873, waiting for three days with members of the Hayden survey in Fairplay, Colorado, for the remainder of the team to join them with the supply train, Jackson explored the surrounding area for photographic opportunities. Jackson recalled, “I climbed Mount Lincoln, twelve miles away, and made a few pictures.” The Cornell Fine Arts Museum’s landscape view by Jackson is the middle section of a three-part panorama taken from Mt. Lincoln showing Quandary Peak and the Blue River Range in the Distance.

As part of Hayden’s 1873 survey team, which focused on the “Four Corners” region of Colorado Jackson’s panoramas added scientific insurance by providing back up in case topographers’ sketches or measurements were faulty. Hayden wrote, “The panoramic views of the mountain peaks have been of great value to the topographer as well as the geologist, and have proved of much interest to the public generally.”

When the survey was completed, in 1879, Jackson opened a photography studio in Denver. He became part owner of the Detroit Photographic & Publishing Co. a firm that printed photographs and stereographic views for wide distribution. In 1893, by default he became the World’s Columbia Exposition official cameraman and exhibited works at the Chicago fair.

Gertrude Käsebier

(American, 1852–1934)The Red Man, 1898

Photogravure print

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.13

Gertrude Käsebier’s The Red Man is her single most famous photograph from her series of images taken of Amerindians performing with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show between 1898 and 1912. Käsebier wrote William F. Cody to receive permission to photograph his performers. The opportunity to photograph Amerindians held resonance for the photographer who grew up in Colorado and as a child had experienced Great Plains Indians. A close-up portrait of the Sioux man, Takes Enemy, with a blanket pulled up around his head and shoulders, The Red Man appeared in the premier issue of Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work in January 1903. Käsebier submitted it to several exhibitions. Her portraits such as those of the Indian performers have a natural and direct quality. In terms of tone and technique, her pictorial style displays soft focus accentuated by platinum and gum bichromate printing.

After her own children were adolescents, Käsebier followed her desire to become a portrait painter. Between 1889 and 1893, she completed art training at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. Concurrently, she developed an interest in photography winning a $50.00 prize in her first successful photographic competition in 1892 sponsored by The Monthly Illustrator. In 1900, she was the first woman invited to join the Linked Ring whose exclusive membership extended to include an international group of photographers.

Käsebier was a founding member in 1902 of the elite American art photographer's association Photo-Secession along with Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, and Clarence White. Although she participated in amateur camera organizations such as the Photo-Secession, she bridged the divide between amateurs and professionals opening a commercial studio on Fifth Avenue near 32nd Street in New York City. Käsebier is renowned for her images of mothers with their children in themes similar to ones articulated in paintings by Mary Cassatt. One was selected to appear in the “Masters of Photography” U.S. postage stamp series in 2002.

Edward Steichen

(American, born in Luxembourg, 1879-1973)Portrait of Clarence White, 1905 (taken before)

Photogravure

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.28

Edward Steichen’s Portrait of Clarence White appeared in the January 1905 issue of Camera Work. Its broad, impressionistic style is characteristic of the soft-focus mode and the newly introduced gum print process favored by art photographers in early twentieth-century America. Steichen’s subject, Clarence H. White (1871-1925) grew up in small towns in Ohio before becoming a bookkeeper, turning to photography after visiting the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. The critic Sadakichi Hartmann wrote, “Clarence H. White of Newark, Ohio sprang into being as an artist with the rapidity of a meteor rushing into space.” After moving to New York City, White taught photography at Columbia University, establishing one of the first university fine art photography programs in America. He was most influential as the founder and director of Clarence White School of Photography established in 1914. His students included Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, and Paul Outerbridge.

Born in Luxembourg, Edward Steichen came to America with his family in 1881 and by 1889 they had settled in Milwaukee. At the age of 15, he apprenticed with a lithographic studio where he began using a camera for lithographic work and to photograph family and friends. A self-taught artist, Steichen’s interest was to become a painter. While in New York City on his way to Paris in 1900, he was introduced to Alfred Stieglitz. A founding member of the Photo-Secession along with Stieglitz, Gertrude Käsebier, and Clarence White, Steichen assisted Stieglitz in the formation of the group’s artistic vehicle Camera Work published 1903-17. Together they opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue, which became known as 291, in what had formerly been Steichen’s studio. With his connections to European painters, Steichen helped to bring artwork by Rodin, Matisse and Picasso to America.

During the First World War, Steichen supervised aerial photography for the American Expeditionary Forces. Between 1923 and 1938, he photographed for Condé Nast publications Vanity Fair and Vogue. His images of celebrities such as Greta Garbo, Gloria Swanson and Gary Cooper epitomize modern fashion photography of their time. He was appointed Director of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art from 1947 to 1961. Considered Steichen’s tour de force, the Family of Man exhibition—503 images by 273 photographers originating in 69 countries opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955 before touring internationally to 88 venues in 37 countries and viewed by 9 million people.

Alfred Stieglitz

(American, 1864–1946)A Snapshot–Paris, 1911

Photogravure

Purchased with funds from the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.26

A Snapshot—Paris depicts everyday realism: a man, his horse and cart standing before piles of wood that they were apparently in the process of transporting. Taken from above the subject matter, this extraordinary treatment of an ordinary vernacular scene was typical of Alfred Stieglitz’s early photographs. Likely taken with a hand camera that was light weight and required no tripod enabled Steiglitz to move silently and quickly so as not to disturb the quiet moment.

One of the most influential figures in the history of photography, Stieglitz was a self-educated photographer having purchased his first camera while living in Berlin studying engineering and photo chemistry in the 1880s. He won several prizes exhibiting his photographs in Europe. After returning to the U.S. in 1890, he joined two friends in a photo-engraving business but became dissatisfied. Because his wife’s family had money, Stieglitz was able to quit the firm to promote photography as a fine art firm.

Stieglitz, who had previously organized the Camera Club of New York City and served as editor of the club journal, Camera Notes, (from 1897-1902) was a strong proponent of “straight” photography. In 1902, he organized an exhibition, American Pictorial Photography Arranged by the Photo-Secession; with this, the group broke away from the Camera Club of New York.

The Photo-Secession, one of the most influential camera organizations, was founded in the U.S. in 1902 by Alfred Stieglitz and several associates.* They chose the name “photo secession” to dramatize their rebellion against the status quo, just as avant-garde German and Austrian painters had used the same word to make manifest their independence. The group was united in disdain for what they perceived as the lack of standards and the general conduct of photographic exhibitions in the United States.

The record of the Photo-Secession is contained in 50 issues of the much-praised Camera Work, published quarterly between 1903 and 1917. In addition to Camera Work, the Photo-Secession had a gallery, which came to be known as 291 from the street number on Fifth Avenue in New York City, where it was located. From 1906 on, the gallery showed not only pictorial photographs but also featured avant-garde modern art, selected at first by Edward Steichen in Paris. Long before the Armory Show of 1913, Stieglitz introduced Americans to paintings and sculpture by Rodin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Picasso, Brancusi, and Matisse.

*Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, and Clarence H. White were also founding members

Paul Strand

(American, 1890–1976)Telephone Poles, 1915

Photogravure print

Purchased with the Michel Roux Acquisitions Fund, 2013.27

The last two issues of Camera Work contained photographs by Paul Strand only. In addition, Alfred Stieglitz mounted an exhibition of his works at Gallery 291. At the age of 17, Strand began to study photography with Lewis Wickes Hine at the Ethical Culture School in New York City. Although Hine’s photography centered on social issues including child labor, industrial workers and immigrants at Ellis Island, he took Strand to meet Stieglitz at 291 where the young photographer was exposed to avant-garde paintings by Picasso, Cézanne, and Braque.

Strand soon rejected the then popular Pictorialist style, which emulated the effects of painting in photographs by manipulating negatives and prints. Instead, he favored achieving the minute detail and rich, subtle tonal range afforded by the use of large-format view cameras. Strand commented on his approach, “It has always been my belief that the true artist, like the true scientist, is a researcher using materials and techniques to dig into the truth and meaning of the world in which he himself lives; and what he creates or, better perhaps, brings back are the objective results of his explorations.”

His new method featured un-manipulated straight photographs, some verging on seeming abstraction. His photograph Telephone Poles appearing in the October 1916 issue of Camera Work exemplifies his investigation of form and light and the abstraction of objects. Strand’s interest in the structure of modern forms led him to collaborate with the Precisionist painter and architectural photographer Charles Sheeler in the making of the short avant-garde film Manhatta, a vision of the modern city released in 1921. Subsequently, Strand purchased an Akeley movie camera and began to work as an independent cinematographer in such government sponsored documentary films as Pare Lorentz’s The Plow that Broke the Plains. Strand’s interest in film making continued well into the early 1940s. After World War II, Strand turned to book publication as a format in which to present his photographs integrated with text, collaborating on Time in New England with Nancy Newhall, and several publications after his relocation to Europe in 1950. Strand’s career in photography and film spanned nearly 70 years.